Somalia’s Persistent Constitutional Disputes: Why They Remain Unresolved

Somalia has operated under a provisional constitution since 2012. That charter mandated a four-year review process tied to the first parliament’s term, with a final constitution approved by referendum by 2016[1].

In practice the 2016 deadline passed unmet. Key elements of federalism remain undefined. Experts note the review “has stalled, and no progress has been made in clarifying the status of the FMS [Federal Member States]” or on power- and resource-sharing between levels of government[2]. Successive governments have struggled to build consensus. Political rivalries, competing visions of government, and persistent security and logistical challenges have kept reforms in limbo.

Federalism and Political Elite Conflicts

The relationship between Mogadishu and its states has repeatedly frayed. Disagreements over the federal structure and disputed territories have fed the broader constitutional deadlock. In 2018–2020 Mogadishu and state leaders briefly agreed in conferences at Jowhar and Baidoa on election rules, justice and security arrangements, and resource-sharing[3].

Those efforts collapsed amid accusations that the federal government was interfering in state politics and marginalizing key governors (notably in Jubaland and Puntland)[3]. In December 2020 President Mohamed Farmaajo formally postponed the review, citing these tensions. His decree deferred the process to the next parliament, blaming “federal government interference” in state elections and the incomplete formation of member states[4][3].

Tensions flared again in 2024. In March 2024, Somalia’s parliament approved a package of amendments that would introduce direct presidential elections and let the president appoint a prime minister without parliament’s consent[5].

Critics argued these changes concentrated power in the presidency. Puntland’s government immediately withdrew recognition of the federal government, insisting that any amendments be approved by a referendum including all member states[5]. This “constitutional crisis” left Puntland effectively acting autonomously[5].

Jubaland likewise broke with Mogadishu later in 2024. In November, Jubaland’s authorities suspended cooperation after the federal government issued an arrest warrant for Jubaland’s president Ahmad Madobe[6]. Each rift reflected deeper elite splits: rival presidents and parties jockeyed for advantage, often treating constitutional change as a zero-sum contest.

Unresolved Federal-State Issues

Fundamental ambiguities in Somalia’s federal design have fueled disputes. The 2012 constitution is vague on many matters, forcing constant negotiation. For example, Somali leaders still dispute how to allocate authority and revenue between Mogadishu and the states, and even whether the capital should have special status[7]. The Bertelsmann Transformation Index notes that 11 years after the provisional charter, “no progress has been made in clarifying the status of the FMS, their main tasks and responsibilities”[2]. Many top politicians believe that solidifying federalism is a prerequisite for a new constitution. But each election cycle brings new leaders. As one expert observed, even already-agreed frameworks (on elections, natural resources, security, etc.) would “need to be renegotiated” because successor leaders refuse deals struck by their predecessors[8]. In effect, every political transition resets parts of the bargain.

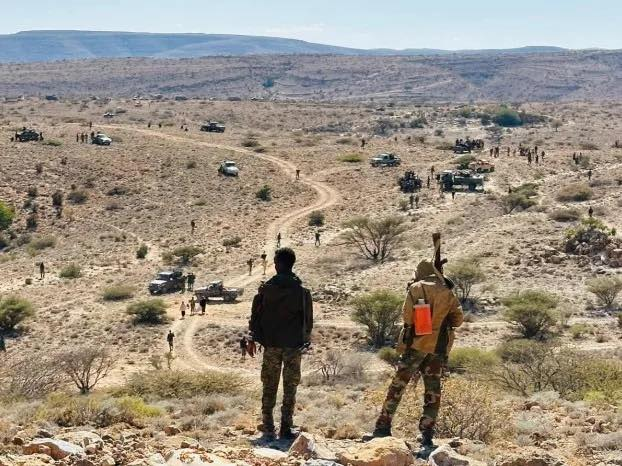

The semi-autonomous governments of Puntland and Jubaland have been particularly assertive. Puntland has demanded that constitutional change be done by consensus and referendum. When Mogadishu pushed ahead unilaterally in 2024, Puntland declared independence from the federal process until a new charter was agreed with its participation[5]. Jubaland’s 2024 break with Mogadishu over an election row showed similar frictions: federal authorities moved troops into Jubaland after its local elections, and Jubaland answered with an arrest warrant for the president of Somalia[6]. Both episodes underscore how federal member states can veto or impede national agreements by refusing to cooperate.

Contest over the Electoral System

A major fault line in Somali politics is the choice of electoral model. Since 1969 Somalia used an indirect, clan-based system: elders pick MPs, who elect the president. Reformers long promised to move to “one person, one vote.” President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud (elected in 2022) made this a key pledge. In August 2024 his government’s cabinet approved legislation to switch to universal suffrage[9]. By November 2024 Parliament had overwhelmingly passed an Election Act enabling one-person-one-vote and creating a multi-party system[10][11]. Under that law the 2026 elections would see Somalis directly elect MPs and the president; three political parties were to be licensed[10][11].

This reform, however, exposed deep divisions. Puntland and Jubaland opposed the changes[12], arguing that the country was not ready for direct voting. They and other critics accused Mohamud of using the reforms to extend leaders’ terms or aggrandize power. Some elder politicians (including former presidents Sharif Ahmed and Farmaajo) labeled the process “unilateral” and raised security and logistical concerns. They even floated plans for a parallel, clan-based vote if the one-person-one-vote plan were imposed[13]. These objections contributed to confusion and delays. For example, though the 2025 agenda called for a move to universal suffrage, Somali authorities still debated details of quota rules and constituency boundaries.

2022–2023 Attempts at Consensus

After Mohamud’s 2022 election victory there was cautious momentum toward resolving outstanding issues. Federal and state leaders convened a National Consultative Council to hash out agreements on federalism. Between late 2022 and mid-2023 the Council reported a series of ad hoc agreements on major topics. For example:

- Justice system federalization – agreed in Mogadishu, Dec. 28, 2022[14].

- Allocation of powers and competences – also Mogadishu, Dec. 28, 2022[14].

- Security sector structure – Baidoa conference, Mar. 15–17, 2023[15].

- Natural resource and revenue sharing – Baidoa, Mar. 15–17, 2023[15].

- Electoral model framework – Mogadishu, May 27, 2023[16].

The May 2023 electoral accord was especially ambitious. It contemplated moving Somalia from its 1960s–era parliamentary model to a fully presidential system, with both a president and a vice-president, and nationwide one-person-one-vote elections[17]. Under the plan only two national parties (the top vote-getters) would contest federal and state elections[18]. This consensus document was to be submitted to Parliament chapter by chapter. Proponents argued that broad buy-in across leaders (including those of all five FMS) would finally make constitutional reform possible[19][20].

In practice, the technical committees prepared a draft amendment, but the political follow-through faltered. Key signatories changed after 2022 state elections, and many new leaders publicly rejected their predecessors’ pacts[8][19].

2024–2025 Escalations and New Negotiations

The situation finally boiled over in 2024, but without resolving the deadlock. In late March 2024 Parliament rushed through the amendments on elections, which Puntland then rejected (see above). Later in 2024 the federal government pressed ahead with one-person-one-vote arrangements despite state objections. In April 2025 Mogadishu launched the country’s first mass voter registration drive in decades[22].

This was billed as preparation for local council elections in June 2025 under a direct vote system. Voters lined up to register, symbolizing hope that universal suffrage might begin. But the rollout encountered political pushback. Prominent opposition figures accused the government of forcing through a model without broad consent. Some opposition leaders publicly suggested they would organize a rival vote if the national process ignored their concerns[13].

Even the opposition camp split in mid-2025. In August 2025 President Mohamud announced an electoral deal with a breakaway faction of senior opposition politicians. This deal largely endorsed the 2024 electoral law but recalibrated it. It reaffirmed that federal MPs (now elected by popular vote) would select the president, and it restored parliament’s right to approve or dismiss the prime minister[23]. It also expanded the definition of political parties (allowing any party with at least 10% of seats to register nationally)[24]. Mohamud hailed this as a path forward.

However, this partial accord ignited further contention. Key opposition leaders outside the deal denounced it. Former President Sharif Ahmed and others warned that Somalia was not secure enough for full direct elections and complained the process still lacked legitimacy[25]. Jubaland and Puntland leaders, again, kept their distance. By mid-August 2025 even inter-party talks had collapsed. A stalled summit was postponed after government and opposition negotiators failed to agree[26]. Observers noted that parties were still deeply split over fundamentals: critics charged Mohamud with “pursuing changes for his benefit” and with trying to collapse federalism[26][27]. In one government statement, opposition factions threatened term extensions under direct voting, illustrating how electoral reform itself had become a tug-of-war over power and tenure[28][29].

Enduring Deadlock and Unresolved Issues

After all these years and negotiations, Somalia’s core constitutional disputes remain unresolved. The planned 2026 polls hang in the balance. Even with a new electoral law on the books, analysts warn it has not been ratified by an agreed constitution and is widely contested. The upcoming local elections (originally scheduled for mid-2025) are being delayed or run in isolation, and no consensus exists on the rules for the next presidential vote. Several fundamental issues are still in limbo:

- Power Sharing. The division of authority between Mogadishu and the FMS has never been locked in. Provinces argue the federal government has overreached, while Mogadishu insists that some centralization is needed. Distribution of security forces, taxation authority, and oversight of justice all remain disputed. Until these are agreed, any new constitution lacks the buy-in of all levels.

- Election Model. Somalia has never conducted the nationwide one-person-one-vote elections that its 2024 law envisages. Doubts about capacity and security persist. Many Somali leaders worry that moving too fast to direct voting – without resolving who wields power under the new model – could destabilize politics rather than stabilize it[28][29].

- Status of Mogadishu. The capital’s role is also debated. Should it have special provisions? Puntland especially fears that a stronger central government means losing influence over the capital region. Mogadishu’s status has featured in every round of talks, yet remains undefined[7].

- Federal Charter Legitimacy. Finally, the question of legitimacy haunts every effort. The provisional constitution itself was meant to be temporary, pending a final charter approved by referendum[1]. No new referendum date is scheduled. Many Somalis view amendments made by parliament as incomplete without a fresh popular mandate. Unless and until a broad national agreement is reached (ideally with input from all states and clans), any patchwork of reforms will likely be seen as imposed.

In short, Somalia’s constitutional deadlock persists because no political bloc has been willing – or able – to bridge these divides. Each major change has triggered counter-moves by rivals. As late as mid-2025, the country remained polarized between those pushing rapid reform and those insisting on broader consultation. The pattern of fragmented talks and failed accords suggests the stalemate will continue unless all sides make fresh compromises. With the scheduled end of the current political term approaching, the unresolved status of the constitution and electoral system means Somalia must again choose between extended provisional rule or a messy leap into an untested voting system.

References:.

1. [1][3][4][7][8][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][30] On the Finalization of the Constitutional Review Process in Somalia | ConstitutionNet

2. http://constitutionnet.org/news/finalization-constitutional-review-process-somalia

3. [2] BTI 2024 Somalia Country Report: BTI 2024

4. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-report/SOM

5. [5] Somalia's Puntland refuses to recognise federal government after disputed constitutional changes | Reuters

7. [6] Somalia's Jubbaland government suspends ties with federal administration | Reuters

9. [9] Somalia's cabinet approves bill for universal suffrage | Reuters

10. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/somalias-cabinet-approves-bill-universal-suffrage-2024-08-08/

11. [10][11][12] Somali parliament passes election legislation for universal suffrage

13. [13][31] Somalia - April 2025 | The Global State of Democracy

14. https://www.idea.int/democracytracker/report/somalia/april-2025

15. [22] Somalia launches first voter registration in capital in 50 years

16. https://www.newarab.com/news/somalia-launches-first-voter-registration-capital-50-years

17. [23][24][25] Somalia: Opposition faction strikes surprise electoral deal with president Hassan Sheikh Mohamud | Somali Guardian

19. [26][27][28][29] Somalia: Talks Stall as Rift Widens Over Constitutional Amendments, Election Model